In Era of COVID-19, Virtual Thesis Defenders Make the Most of It

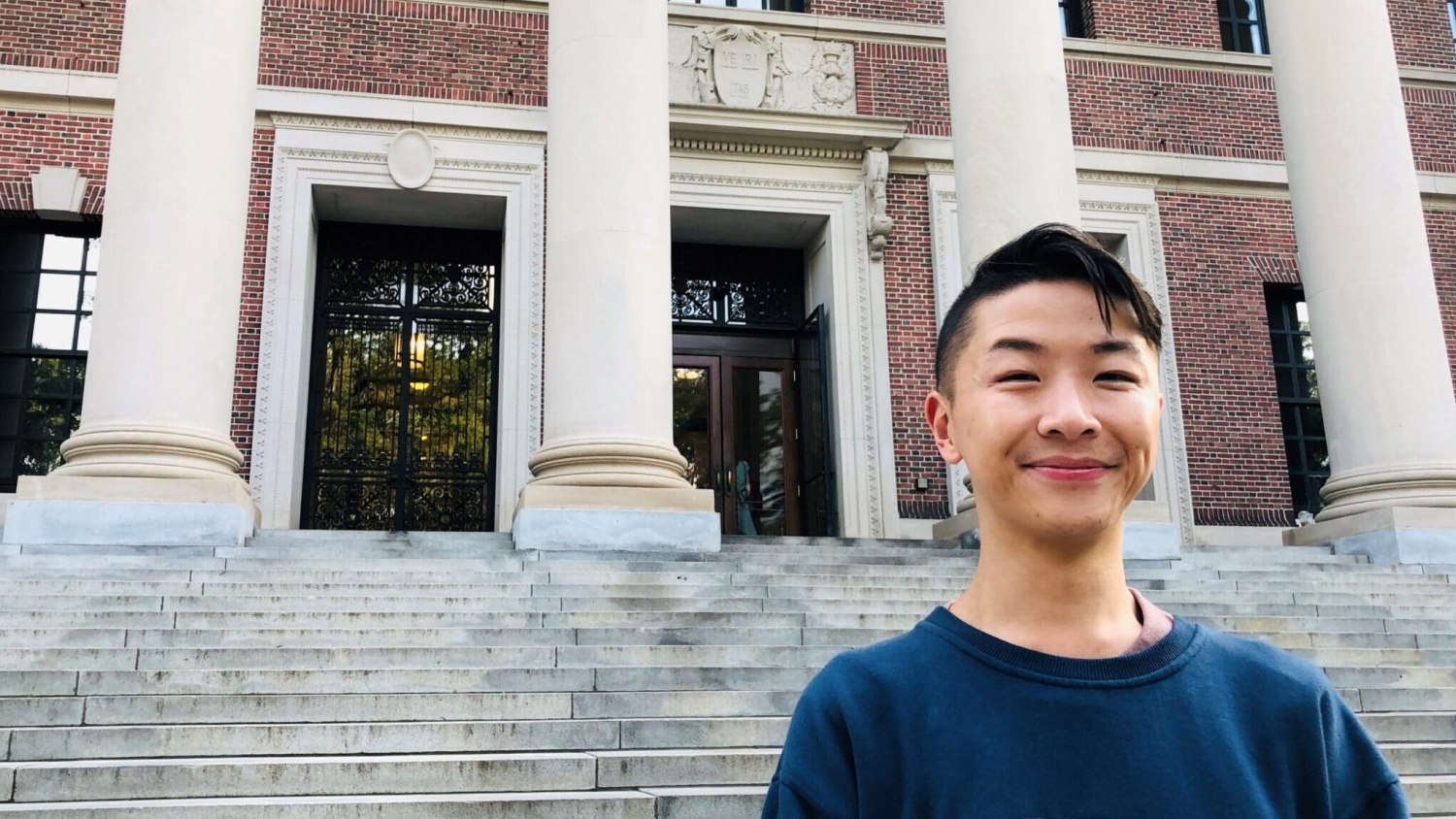

Eugene Cheung had prepared for everything before his thesis defense. For more than a decade he had cultivated an interest in aquatic life. Now, the graduate student in the Department of Biological Sciences was about to defend all his hard work of the past few years before his thesis committee. He had double-checked his notes, readied his remarks and invited almost 150 friends, relatives and mentors from across North America to watch him.

“I would have preferred to defend in person,” said Cheung. “But I figured if we had this opportunity, I was going to make the most of it.”

Cheung is one of the many graduate students whose academic careers have been upended by the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced students across the country to defend their theses and dissertations online, rather than in-person in front of a small committee and perhaps a few guests. Despite the difficulties presented by video conferencing platforms and sometimes spotty Internet connections, students are taking advantage of the online format to allow far more people to attend their defenses than previously would have been feasible.

Katherine Allen, a graduate student in the Department of Statistics, defended her Ph.D. dissertation in August. Due to the online format, far-flung guests were able to watch the culmination of years of hard work.

“My family and friends are spread all across the U.S. and would not have been able to attend were the defense in person,” Allen said. “While I wish I could have defended in person and that [COVID-19] had never happened, I am grateful those folks who would not have been able to attend my defense otherwise attended.”

Allen cited some of the pros of an online defense: lower stress, presenting in a familiar space, and, she noted, no high heels.

There were some aspects Allen missed.

“I really wanted to see [the thesis committee] in person,” she said. “I wanted to shake their hands.”

“While I wish I could have defended in person and that [COVID-19] had never happened, I am grateful those folks who would not have been able to attend my defense otherwise attended.”

For Cheung, having family and mentors from his native Canada watch him defend was something that would have been impossible if the defense wasn’t held online. Among his invitees was his now-retired middle school science teacher Michael Neilands.

“When I sat in during Eugene’s defense,” Neilands said, “I couldn’t believe his incredible knowledge of [his thesis], and how much respect he commanded.”

Neilands, who inspired Cheung to go into the sciences, does not usually get to see the students he teaches after they leave. For him, seeing Cheung defend was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

The father of Craig Jensen, a graduate student in the Department of Marine, Earth, and Atmospheric Sciences, also would not have been able to attend his son’s defense if it were held in person. Not only was Jensen’s father in another state, he was also busy at the time.

“My dad, who’s back in Michigan, was able to attend [my defense]. Only thing is, it was during his work day,” Jensen said. “I had assumed he wouldn’t be able to come, but there he was when I was ready to start. Turned out that he logged into the Zoom call on his phone and was covertly listening to it, unbeknownst to his supervisors. He was willing to get in trouble with his boss just to see me defend.”

Another of the almost 150 people Cheung invited to his defense was Victor Navarro, an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard University, where Cheung is now a research fellow. Cheung met Navarro at a seminar in New York after having previously read his work.

“I was impressed by him,” Cheung said. “He was extremely nice in person, and spent a lot of time talking to me.”

Cheung met with Navarro again, having traveled to Boston to talk to him. Cheung said Navarro’s staff was nothing but supportive, and Navarro himself encouraged him to stick with the sciences during a difficult time in Cheung’s life, and to keep Navarro updated on his accomplishments.

It meant the world to Cheung to have people like Navarro and Neilands attend his defense. For Neilands, the retired middle school science teacher, it meant even more than that.

“I always wanted students to know how much I cared about them,” Neilands said. “I cared about their well-being and always had their best interests in mind. Seeing Eugene again reminded me of the quiet, respectful, well-behaved student with a great sense of humor and a natural inquisitiveness. [He] was a student who didn’t just want to learn, but to understand.”

This post was originally published in College of Sciences News.