BioSci’s Bones: Ann Ross and the Forensic Analysis Lab

By Kathleen Wilson

By Kathleen Wilson

Last summer BioSci got an unbelievable deal after Professor of Forensic Anthropology, Ann Ross, set her sights on joining our department. Formerly in the Anthropology department of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Ann found her science to be more in line with ours, and after an easy vote in support of her request, BioSci’s Department Voting Faculty welcomed her with open arms. As one of only 119 diplomats of the American Board of Forensic Anthropology, Ann and her lab bring a unique element to the department. In June she was good enough to host our admin staff for a tour of her lab, where we got a first-hand look at exactly why her work is so celebrated.

“Hi!” The door to Ann’s lab swings open as she welcomes us in from the heat. We’re led to a logbook in which all visitors must sign in and out, granted the active forensic cases Ann has in and out of her lab. Each of us scan the lab tables like eager kids as we shuffle in. Three contain bones. Two of those three are active forensic cases, one of which is that of 74-year-old Carolyn Sue Fox, who went missing in July of 2016, and was found buried behind her Wendell home in March. Having followed it on the news, I ask if this is the case in which the victim’s son is the lead suspect. “Yeah, the [individual] believed to be involved in her disappearance? Yes,” she confirms. Carolyn’s bones are neatly laid out with meticulous care, her tiny jaw baring a dental bridge, somehow re-personifying the beige sticks and bobbles of her remains. Ann points out the injuries Carolyn sustained, noting the cause each one indicates while our group looks on in fascination. As she speaks, two things captivate me: First, her poker-faced professionalism and expertise on a subject many consider grotesque and deeply upsetting, and second, the simultaneous compassion she shows for the victim, and others in her care.

As her lab holds the NC Office of the Chief Medical Examiner contract through the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services for all forensic anthropological cases, one might expect Ann to be desensitized to her work. On the contrary, she tells me cases still get to her. “Absolutely, particularly those involving child abuse. If I also have a perplexing case, generally trauma, I mull over the case in my sleep.” The 2010 life-sentencing of Sherita Nicole McNeil, a Garner mother who abused and eventually murdered her 19-month-old son, DeVarion Gross, marked the first time Ann’s work led to a murder conviction. “I was glad I was able to speak for him and be his voice,” she recalls. Perhaps it’s these voices that create the public’s fascination with Ann’s field. The ones silenced by their murderers, speaking through the diligence and dedication of these scientists. When she and her team succeed in obtaining justice in these cases, she states, “I just feel a sense of relief for the family of the victim.”

As her lab holds the NC Office of the Chief Medical Examiner contract through the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services for all forensic anthropological cases, one might expect Ann to be desensitized to her work. On the contrary, she tells me cases still get to her. “Absolutely, particularly those involving child abuse. If I also have a perplexing case, generally trauma, I mull over the case in my sleep.” The 2010 life-sentencing of Sherita Nicole McNeil, a Garner mother who abused and eventually murdered her 19-month-old son, DeVarion Gross, marked the first time Ann’s work led to a murder conviction. “I was glad I was able to speak for him and be his voice,” she recalls. Perhaps it’s these voices that create the public’s fascination with Ann’s field. The ones silenced by their murderers, speaking through the diligence and dedication of these scientists. When she and her team succeed in obtaining justice in these cases, she states, “I just feel a sense of relief for the family of the victim.”

In addition to this solemn perspective, Ann also provided our group with some fun facts about her field, as well as North Carolina. For example: Ann tells us she’s seen more dismemberment cases in NC than anywhere else in her career. And as she showed us, we get really creative, giving a whole new meaning to NC’s ability to ‘think and do.’

As she explains, there are three main reasons for dismemberment: Transportation, concealing identity, and abhorrence for the victim. “We’ve seen all three types in the lab, but I would say that ease of transportation is probably the most common as there is a reason to the saying ‘dead weight’.”

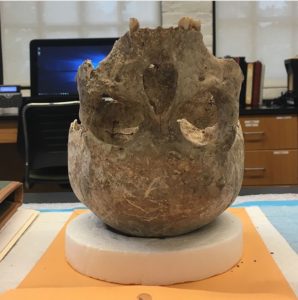

One such case was that of Laura Ackerson, which made international headlines in 2011 after the Raleigh mother’s remains were found in a creek 60 miles south of Houston, Texas. Now household names to many, Grant and Amanda Hayes were convicted of killing, dismembering and transporting Ackerson to Texas after a nasty custody battle over Ackerson and Hayes’ two sons. Shortly after the murder, Amanda Hayes’ daughter found an instruction manual for a power saw in her mother’s apartment, and turned it over to police. Ann’s team was then able to test the same saw on pig remains, confirming the marks matched those found on Ackerson’s bones. “This was the first time we used pig proxies to test weapons used in a dismemberment, which is now part of my lab’s SOP’s,” Ann notes. Grant Hayes was convicted of first-degree murder. Amanda Hayes, second.

One such case was that of Laura Ackerson, which made international headlines in 2011 after the Raleigh mother’s remains were found in a creek 60 miles south of Houston, Texas. Now household names to many, Grant and Amanda Hayes were convicted of killing, dismembering and transporting Ackerson to Texas after a nasty custody battle over Ackerson and Hayes’ two sons. Shortly after the murder, Amanda Hayes’ daughter found an instruction manual for a power saw in her mother’s apartment, and turned it over to police. Ann’s team was then able to test the same saw on pig remains, confirming the marks matched those found on Ackerson’s bones. “This was the first time we used pig proxies to test weapons used in a dismemberment, which is now part of my lab’s SOP’s,” Ann notes. Grant Hayes was convicted of first-degree murder. Amanda Hayes, second.

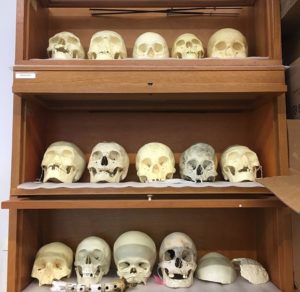

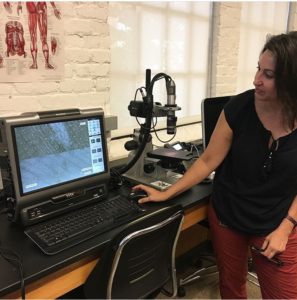

Another practice Ann has developed is geometric morphometrics, in which cranial bones are mapped three-dimensionally in what are essentially constellations, and stored in a database she’s created (3D-ID), providing a wealth of knowledge on age, ancestry, sex, and various other characteristics used by forensic scientists for identification. Using geometric morphometric tools, the user uploads anatomical coordinates from the subject, after which the program matches it with any similar subjects found in the database, and ultimately assigns it to a group. Thanks to Ann and her collaborators forensic scientists across the globe have access to this invaluable resource.

Another practice Ann has developed is geometric morphometrics, in which cranial bones are mapped three-dimensionally in what are essentially constellations, and stored in a database she’s created (3D-ID), providing a wealth of knowledge on age, ancestry, sex, and various other characteristics used by forensic scientists for identification. Using geometric morphometric tools, the user uploads anatomical coordinates from the subject, after which the program matches it with any similar subjects found in the database, and ultimately assigns it to a group. Thanks to Ann and her collaborators forensic scientists across the globe have access to this invaluable resource.

Even with cutting-edge technology like this, sometimes more organic methods are needed for their work. When Ann asks if we want to see the “flesh-eating beetles” my mind jumps to something belonging in a Guillermo del Toro film. On the contrary and to our surprise (and a little relief), Dermestidae are tiny, innocuous little guys, about a half-inch long. Used in the lab to produce clean, undamaged bones much faster than decomposition alone, the beetles provide a great service to Ann and her team. At the time of our visit, Ann’s colony was snacking on a piece of pig fresh from NCSU’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, which donates all specimens used in the lab.

On the subject of these piggies and their noble purpose in Ann’s lab, I ask her if she listens to any music while hard at work testing murder weapons on them, and if so, what. With a smirk she replies no, but tells us her favorite genre is alternative, which she does listen to while contemplating cases. Her favorites include Of Monsters and Men, Cage the Elephant, Twenty One Pilots, Sylvan Esso and Kate Nash.

With dismemberment simulation, skull constellations, flesh-eating beetles, and other fascinating goings-on in her lab, it’s no wonder the public is in awe of Ann’s profession. Often referred to as NCSU’s real-life Bones, I ask her how true-to-life she finds the popular TV show to be compared to her own work. “First of all, I never have the opportunity to beat up people with martial arts and I don’t have a hologram that reenacts the homicide,” she laughs. “In one of the first episodes they could tell the decedent was pregnant as they found ear bones from the fetus. This put me off as the ear bones are the only ones that are adult shape out all 206 bones in the skeleton!” She knows her stuff. Click here to learn more about Ann and NCSU’s Forensic Analysis Laboratory.

- Categories: